View live flow and water level readings for Lambert Creek at the Lambert Creek waterbody page.

View a presentation and download the report from a Lambert Creek Repair Survey completed in 2018.

Why does our watershed drain the way it does?

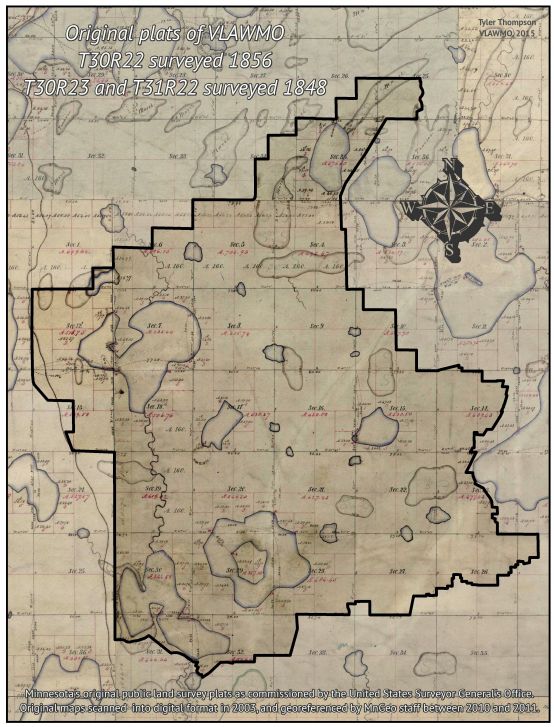

Wetlands in VLAWMO were formed 9,000-12,000 years ago by glacial activity. As the glaciers receded, depressions and glacial out wash were left on the land. Unlike deep glacial pothole lakes in northern Minnesota, the melt water and sediment dispersal in this region was relatively flat. These areas are where we find wetlands today.

A wetland is an area where water either covers the soil or is present near the surface. A wetland can hold water year-round or just part of the year, both of which influence vegetation, storage capacity, and local hydrology.

While wetlands have been avoided and looked down upon for many years, they're also a part of the Vadnais Lake area history. They are the original flood control infrastructure, a natural purifier for drinking water, valuable wildlife habitat, and they replenish groundwater for the future.

As seen in the map below, the VLAWMO watershed was historically a region of shallow lakes and wetlands. Upland areas consisted of wet meadow, prairie, oak savannah, and deciduous/mixed forest. Throughout the past 100 years, the region has largely been modified through drainage, channelization, and ditching as agriculture gave way to urban development. Some shallow lakes such as Lambert Lake no longer exist due to drainage, and many historic wetlands were filled and built upon. Some wetlands were transformed and consolidated into shallow lakes by filling their outlets and draining surrounding ponds and wetlands into them. While these changes weren't made with mal intent, they were also short-sighted for the needs and health of water resources.

1940's-era Ramsey County Drainage Map

Shallow Groundwater

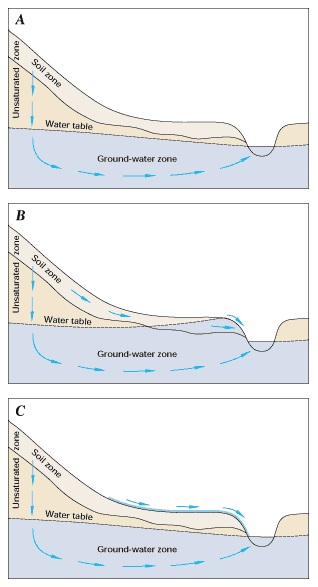

More than 50% of Minnesota contains shallow groundwater, a condition where a high groundwater table (saturated soil) is near the land’s surface. This is often indicated by the presence of wetlands. Unlike deep ground water, shallow groundwater moves according to gravity across the earth’s surface. Soil exposed to shallow groundwater becomes anaerobic, or hydric. While the water table changes year to year depending on rainfall and surface runoff, hydric soils retain the same chemical composure after shallow groundwater levels recede (part B in diagram below). When high rainfall follows a dry period, hydric soils quickly go back to acting like a wetland. While areas with wet soil can be a nuisance, it's important that the boundaries of our wetlands and floodplains are maintained and respected because they are a crucial part of the water cycle.

Diagram courtesy of USGS

What does dredging entail?

As ditch authority under Minnesota Statute 103B, VLAWMO is responsible for maintaining a reasonable function of the ditches and waterways in the Watershed. A 2018 feasibility study and Repair Report for Ditch 14 determined that the Ditch was adequately functioning and dredging repair urgency is not immediate, but should be planned and budgeted for. Click here for a list of reports and presentations on Lambert Creek/Ditch 14.

VLAWMO plans for ditch repairs and cleaning efforts with its member communities. While dredging portions of Lambert Creek or its branch ditches is possible, it's not always a cost-effective option. High water levels and debris accumulation are monitored to maintain efficient flow rates.

Living near a wetland or ditch can require some patience and flexibility. While it may be tricky to maintain a green lawn in such areas, it is possible to live in harmony with wetlands and floodplains. With some planning and patience, VLAWMO is here to help create solutions that work for both people and water resources. Options include:

Every property has factors that could call for one or a combination of these strategies. Contact (651) 204-6071 to request a free on-site visit from VLAWMO staff to discuss your needs and the possibilities for your yard.

History of MN Drainage Policy:

The issues we face today are a reflection of our history with water. Understanding where we’ve been helps us face today’s challenges. See the BWSR history and DNR history web pages for more on this topic.

- 1883: Drainage ditches were used in the Vadnais Lake area as a means to keep agricultural lands reliant and productive. In the late 1800’s, “public water” consisted only of waters that contained uses such as fishing, boating, or drinking water. Other waters such as shallow lakes and wetlands were considered “private” and therefore were unprotected.

- 1920’s: Ramsey County takes responsibility of a key drainage ditch which would be called County Ditch 14, now referred to as Lambert Creek. Many small agricultural ditches remained, and were maintained privately.

- 1937: All water in the state becomes public waters. In the wake of the great depression, Roosevelt’s New Deal included initiatives to include natural systems in our city planning and development. While the practice of ditching worked to limit the water in the soil, allowing it to be more readily planted, this practice also contributed to the conditions that created the dust bowl. While there was controversy during this shift, this policy recognized the importance of shallow lakes and wetlands for the longevity of society.

- 1947: Limits were set onto the drainage of public waters. Drainage could only occur in “non-public” settings and only with permission.

- 1955: Conservation and President Roosevelt's New Deal was brought into drainage policy. This protected water bodies such as Goose Lake, which is an example of a water body that was directly used as a waste water dump site. Unfortunately, this dumping was a common practice at the time.

- 1982: Metro Area Surface Water Management Act. This act created the need for a mandatory governing body, a water management organization (WMO) to manage surface waters. A WMO is responsible for creating comprehensive water management plans that seek to protect and improve surface and groundwater quality, prevent erosion, correct water quality problems, and others. See the MPCA watershed plan website for more information.

- 1986: Ramsey County transfers authority of Ditch 13 and 14 (Lambert Creek) onto VLAWMO. Today VLAWMO partners with its municipalities to conduct improvement projects and maintain the ditches.

- 1991: Wetland Conservation Act. A “no net-loss” is instated for MN wetlands to protect our abundant and clean water resources. Wetlands, deemed so by specific guiding principles, must be replaced either locally or elsewhere in the state through the purchase of banking credits.

- 2015: MN Buffer law. Requirements were set for permanent vegetative buffers on public waters and public ditches. These buffers serve to reduce erosion, excess nutrients, and pollution going into our waters.

- 2016: Governor Dayton issues the “year of water” decree.