Shallow Lakes, Wetlands, and Buffers

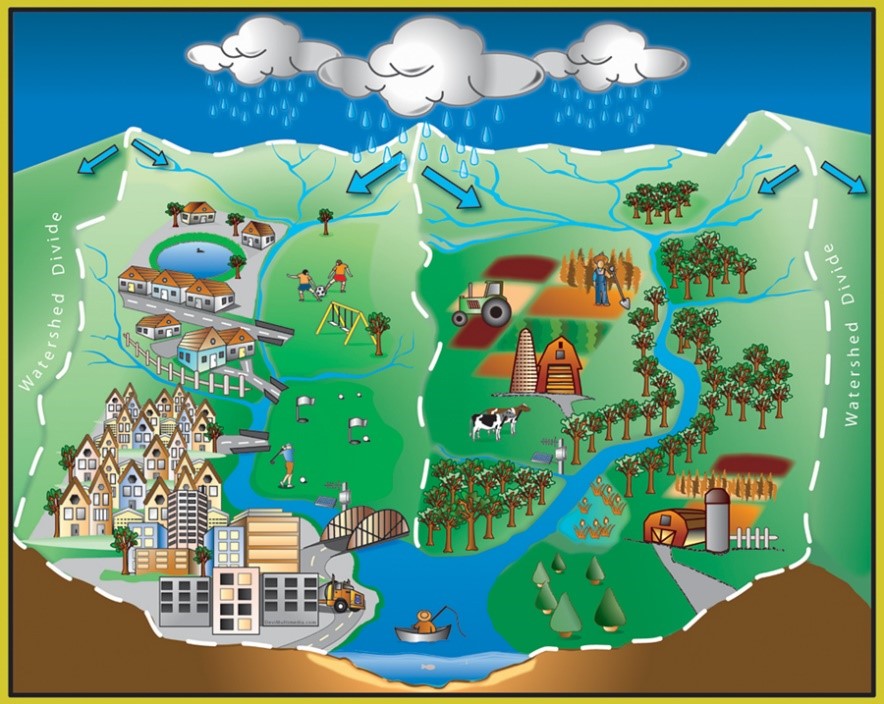

A watershed is all the land area that drains to a specific water resource, such as a lake or river. Watersheds range in size from a few square miles to an entire continent. There can be smaller watersheds within larger ones, such as VLAWMO being a small subset of the larger Mississippi River watershed. VLAWMO is divided into smaller sub watersheds, as seen below. As rainwater and melting snow run downhill, they carry sediment and other materials into streams, lakes, and groundwater.

96% of the land use within VLAWMO is urban, with a small agricultural area at the northern end. Because the urban landscape heavily changes the flow, drainage, and evaporation of the water cycle, our challenge is to create harmony between the two. Understanding how watersheds and wetlands work can help us live, work, and play in ways that benefit the water cycle.

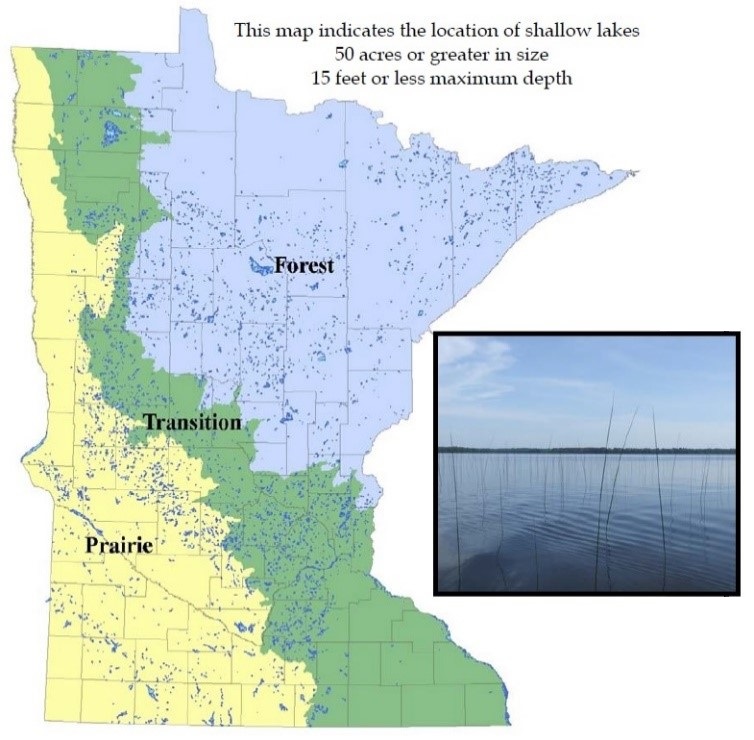

Shallow lakes fall on a spectrum between deep lakes and wetlands. Unlike the deep lakes of Northern Minnesota where aquatic plants are found in a ring around the shoreline, shallow lakes contain plants over most of the lake bed. This is largely because sunlight reaches the bottom of shallow lakes, allowing plants to grow. This also influences lake temperature and the mixing of nutrients and sediment. While deep lakes turnover in the winter and mix nutrients as the water cools in the winter, shallow lakes are continually mixing throughout the summer. This creates a fragile environment that can sway between healthy and unhealthy depending on the management of the water. Click here to see a video about shallow lakes.

Regions with shallow lakes and wetlands also coincide with shallow groundwater, also known as the water table. In transitionary regions such as central Minnesota and the Twin Cities (see diagram below), the water table is subject to dynamic changes depending on rainfall. Soils in our region respond to this ebb and flow of water, retaining its ability to act like a sponge. When exposed to saturation for long periods, soils become hydric and change their chemical composition. Even after decades of being dry, hydric soils will retain water rather than drain it when re-exposed to a high water table. With the complex, dynamic nature of wetlands, it can be difficult to establish clear-cut boundaries around them. Buffers are a natural and helpful way to separate wetland and upland areas. Plants within a buffer help uptake the excess water in the soil, and provide space for flexibility and adaptability to changes in the water table.

As surface runoff and storm systems direct water into our shallow lakes, there is a continual struggle for balance. In a healthy state, shallow lakes are abundant with fish, birds, and vegetation. With too much sediment and nutrients, they quickly become dominated by algae and limit the potential for other organisms. This murky water is known as a turbid state, and raises the risk for our long-term water resources. When a lake flips into this state, it's very difficult to turn it back to a clean water state. Unfortunately, an estimated 40% of Minnesota's water bodies are listed as "impaired", in a degraded or turbid state.

Helping our shallow lakes can be easy and fun with a community effort – visit our water stewardship at home page to learn how you can be a part of a secure water future.

While wetlands are present across North America, they are most abundant in the north-central US and Southeastern coastal regions. As seen in the map below, the greater Twin Cities Metro is within a region rich in wetlands.

In the water cycle, wetlands act as a sponge that slows the movement of water. Living with wetlands is living with change. Changing water levels create a system for nutrient cycling, decomposition, filtration, and groundwater recharge. This system is similar to a factory that goes through different production, packaging, and shipping cycles. Each cycle is a part of a wetland's benefit to the long-term health of our water resources. Other benefits that wetlands offer include:

- Climate and temperature control

- Phosphorus, nitrogen, and carbon storage

- Removal of excess metals and certain toxins from water

- Improvement of air quality

- Stabilization of shallow groundwater during dry periods

- Natural buffer between wet and dry areas

- Food and shelter for fish, mammals, insects, and birds

- Support for recreation in fishing and hunting

- Aesthetic open space for communities

While urban storm systems and pavement function with speed and efficiency to keep neighborhoods dry, they also compromise the water cycle that provides abundant, clean water. The increase of pavement has brought new challenges in water quality and quantity. Visit our waterbodies tab for more links and information on VLAWMO's wetlands.

A strip of natural, native vegetation is an asset for lakes and wetlands. Buffers provide deep roots and more surface cover to hold water and soil in place, providing slow movement of water into the lake or wetland. This is an advantage because erosion is reduced, fewer nutrients wash into the water, and habitat is improved. Keeping sediment and nutrients on land and out of the water prevents strong algae blooms, and keeps wetlands functioning well for groundwater infiltration. Click here for more information and diagrams on buffers.

A strip of natural, native vegetation is an asset for lakes and wetlands. Buffers provide deep roots and more surface cover to hold water and soil in place, providing slow movement of water into the lake or wetland. This is an advantage because erosion is reduced, fewer nutrients wash into the water, and habitat is improved. Keeping sediment and nutrients on land and out of the water prevents strong algae blooms, and keeps wetlands functioning well for groundwater infiltration. Click here for more information and diagrams on buffers.

Contact us

Contact us

Phone: (651) 204-6070

Fax: (651) 204-6173

Email: office@vlawmo.org